On Gaian Systems

Asijit Datta interviewed literature and science scholar Bruce Clarke during a webinar on August 27, 2021. Their conversation centered on Clarke’s presentation and development of Lynn Margulis’s neocybernetic approach to the Gaia concept in Gaian Systems: Lynn Margulis, Neocybernetics, and the End of the Anthropocene, published by the University of Minnesota Press in 2020. Often seen as an outlier in science since its debut in the 1970s by atmospheric chemist James Lovelock and evolutionary theorist Lynn Margulis, Gaia theory has run a long and varied course, gradually bringing the Earth and life sciences into closer integration around new understandings of planetary dynamics. This interview explores the development of Gaia’s scientific variants and some key theoretical frames that have been brought to bear on Gaia discourse. Particular attention is paid to Margulis’s adaptation of the concept of autopoiesis, which she viewed as providing a clarifying criterion for the autonomous self-production and symbiotic collaboration of living systems, in contrast to the first-order and computational cybernetics of control systems favored by Lovelock. Clarke’s own work in this area extends Margulis’s autopoietic approach to the Gaian system.

Key points:

- Gaia operates as a continuous loop with components that are not indestructible. It has a fixed volume of matter that cycles through living processes.

- Gaia's "sentience" refers to its ability to maintain itself in response to internal and external environments, not human-like meaning making.

- Gaia constructs its own continuation as an autopoietic system, not due to theology. It lacks an absolute ontological ground.

- Humans are not essential to Gaia which will continue without us. Our activities are "petty" relative to planetary scales.

- Gaia is best understood as a metabiotic system coupling biotic and abiotic components, not just biotic autopoiesis.

- Sympoiesis emphasizes symbiosis but lacks the operational closure of autopoietic systems theory.

- Gaia produces habitability for life but does not ensure easy survival. We must get right with Gaia to remain viable.

- The metaphor of Gaia "within us" refers to mutualistic immunological processes, not literal identity.

- Humans are failing as holobionts by disrupting conditions needed by other species.

For an undergraduate:

- Gaia works like a continuous loop, with parts that can break down and be replaced. It has a fixed amount of matter that cycles through living things.

- Gaia's "awareness" means its ability to maintain itself in response to inner and outer environments, not human-like meaning-making.

- Gaia constructs its own continuation as a self-producing system, not due to theology. It lacks an absolute grounding in a greater being.

- Humans are not essential to Gaia which will keep going without us. Our activities are "minor" compared to planetary scales.

- Gaia is best seen as a combined system linking living and non-living parts, not just living self-production.

- Joint creation emphasizes symbiosis but lacks the closed loop of systems theory.

- Gaia enables habitability for life but does not ensure easy survival. We must reconnect with Gaia to stay viable.

- The metaphor of Gaia "inside us" refers to cooperative immune activities, not literal sameness.

- Humans are failing as combined organisms by disrupting what other species need.

Asijit Datta: Professor Clarke, when you point to Lovelock’s “circular logic” [Clarke 2020, 6] concerning Gaia, as that recursive logic is understood in second-order cybernetics, are you looking at Gaia as a system operated by a continuous loop whose essential components are indestructible? Do you think that Gaia has a fixed volume of unalterable properties, while other components keep metamorphosing?

Bruce Clarke: Yes, a continuous loop would conform to my idea here. However, that such a continuous loop and its essential components are indestructible is not the Gaia conception as I understand it. Matter and energy enter the state of living form, and the components of living systems are always re-forming and breaking down again. Their elements are renewable, but their forms are not indestructible, and the system carries out the continuous creation and de-creation of the productions of the system. That would be one way to state Gaia’s circular logic. Moreover, Gaia itself is not indestructible, but it makes sense to think that it has maintained itself in operation since it got going some two and a half billion years ago. A time will come when cosmological conditions are no longer sustainable for this planetary system, at which point the continuation of life will cease.

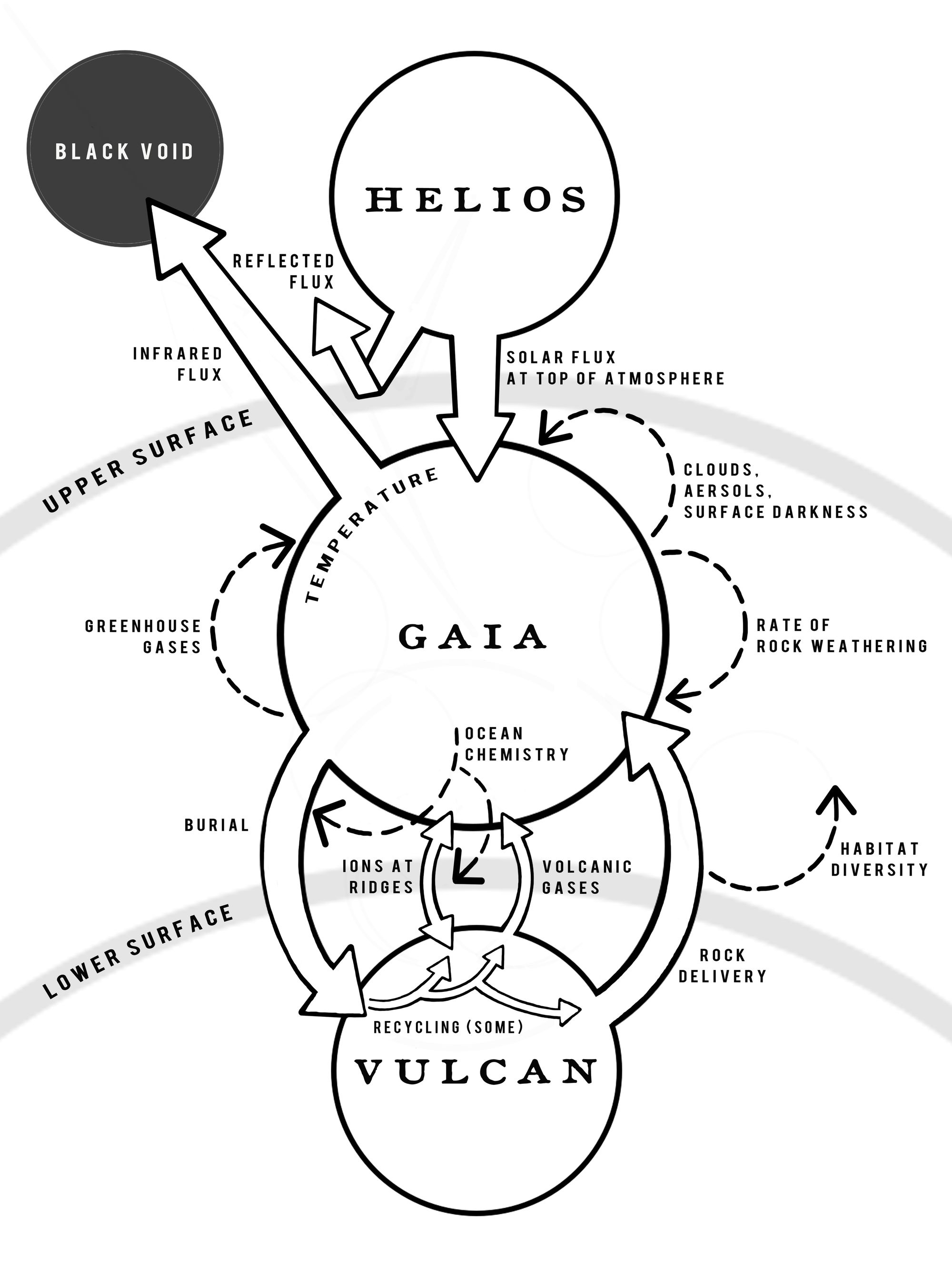

As for a fixed volume, this is the issue of material closure [Barlow and Volk 1990]. The planet is thermodynamically open to the flux of solar energy, of course, even while it is essentially closed to the influx of matter from beyond the Earth, just because this amount is negligible in relation to the total mass of the Earth. So basically, the planet does have a fixed volume of geological matter to be brought into the recycling dynamics that sustain the Gaian system. Gaia itself is also evolving as part and parcel of the interlocking of geological and biological evolution. Gaia continuously reinvents itself, but the operational closure—as opposed to material closure—that comes with the autopoietic conception of Gaia would seem to be a constant element, in a systems-theoretical view, a continuity in the reconstruction of the unity of Gaia altogether.

AD: A lot has been written regarding Gaia’s shape, size, and properties. How do you visualize Gaia?

BC: To form an image of Gaia, the system, I borrow an approach from Tyler Volk’s Gaia’s Body [2003, 77], where he came up with a visualization that I like very much and which I present in my own book. Here, we grant that Gaia as a self-bounded system has surfaces and then diagram it as a film or a planetary bubble pressed upon the surface of the Earth’s sphere. This is akin to what Bruno Latour calls the “critical zone” [2017, 93; Arènes, Latour, and Gaillardet 2018].

.

Gaia itself is not a sphere; rather, it is a planetary film averaging twenty kilometers in breadth. The atmosphere forms the outer or “dorsal” surface stretching up to where the diffuse upper edge attenuates into space. And the ventral surface is the floor of the biosphere that now dives into the crust and the mantle of the planet. In “Gaia and Her Microbiome,” John Stolz [2017] discusses “microbial dark matter,” all this still undiscovered microbial life deep within the Earth’s mantle. Life is going on at a deeper depth than we ever imagined, and that complicates the image of Gaia’s nether surface. Gaia does not have a membrane the way that a cell has a membrane, because its boundaries are diffuse rather than compact. Nevertheless, as we go up or down from where we stand, we move through Gaia until we arrive at realms where Gaia has been left behind. The way I say it is that while Gaia does not have a membrane, Gaia is a membrane, a planetary bubble twelve miles thick that is all membrane, encompassing the Earth, on the inside of which life must find its place [Clarke 2020, 222].

AD: While discussing the autopoiesis of cellular life, Margulis uses an intriguing term, “sentience.” What is this “sense-making” or proprioception? Is it linked simply to the survival of the agent or its finding an indigenous space by modifying the immediate environment, what Bruno Latour calls “distributed intentionality” [2017, 98]? Or are we also attacking the anthropocentric centrality of man’s consciousness and powers of “sense-creating”? Does this conception of sentience oppose human to cellular life, or draw them together?

BC: When Margulis applies the term “sentience” to living systems, I understand this as her way of naming what Maturana and Varela [1980], the initial theorists of autopoiesis, called cognition. They said “autopoiesis is cognition,” to mean that an autopoietic system, even at the basal level of a biological cell, is in a cognitive relation to its environment. For instance, her book with Dorion Sagan What Is Life? has a final chapter called “Sentient Symphony” [2000, 212–43], which is a beautiful metaphor for Gaia. Their sentient symphony evokes all the multifarious sentient entities, living beings, that also have this ultimate connection within a planetary system.

Now, your phrase “finding an indigenous space by modifying the immediate environment” is a good Gaian formulation, and Latour’s idea of Gaia’s “distributed intentionality” could be taken as his way of indicating “sense-making” or autopoietic sentience. But we humans in particular carry out sense-making in terms of what we call meaning, that is, in terms of our form of mentation over and above our survival as living beings. Still, to me the beauty of Gaia in post-humanist terms is its displacing of the anthropocentric centrality of human consciousness. And the resistance to Gaia has had a lot to do with its straightforward displacement of the human from atop the rest of the planet as conceived in classical humanist terms in the Western tradition.

AD: Regarding what you call Gaia’s “planetary cognition” [Clarke 2020, 43, 93], how much of it depends on nonperforming metabiotic actants, such as a stone? What is the performance of the stone that does not have an immediate impact as it cannot move on its own and is acted upon? What is its impact on Gaia?

BC: My idea of planetary cognition is an intuitive step from Margulis’s conception of autopoietic Gaia [Clarke 2020, chap. 6; Margulis 1990]. If Gaia is autopoietic, then this planetary system is cognitive in some fashion, because that description comes along with the concept of autopoiesis. The geological component is an element in the totality of this process. Gaia is cognitive, or sentient, but that does not mean Gaia has thoughts. It is not making meaning for itself; rather, it succeeds in maintaining itself from moment to moment in responsive relation to its external and internal environments. In my own take on Margulis’s theorization, Gaia’s autopoiesis is driven from the biological components of the system: the cognitive element is contributed by the living systems. In the metabiotic conception of Gaia that I have pursued, the geological component is the reservoir of the material elements that must be available to living systems to carry out their own autopoieses. At the planetary level, you have plate tectonics and the continuous recycling of the stony matter of the planet, on the surface and in the mantle, and as driven by the heat energy coming up from the core of the planet [Sleep, Bird, and Pope 2012]. And we know that plate tectonics are part of the necessary environment of Gaia, and may well be a Gaian phenomenon, which circularity would make good Gaian sense.

The Gaian literature also has a robust discussion of rock weathering [Schwartzman and Volk 1989; Stolz 2017]. Here the living components of the system—especially the microcosm, the bacterial component of the biosphere, including the lichens and fungi—interact with the stony matter that emerges to the surface of the planet, immediately as it encounters the biosphere. Over geological time, the biosphere breaks down the rocks and releases the elements locked up there for biological uptake. Also, much stony matter results from biological processes—this is called biomineralization [Westbroek and De Jong 1983; Margulis and Sagan 2000, 25–29, 163–67]. Much of the stony crust is itself biogenic, and it is then further churned through Gaian processes, subducted back down to the mantle, metamorphosed in some geological fashion, and then returned to the crust. So we have this very profound, continuous geological cycling that is part of the total dynamism of the planet and that then interfaces with biological dynamics in all kinds of pathways.

AD: On the one hand, you agree with Margulis’s claim about the sentience of living organisms; on the other hand, you support the neocybernetic postulation that Gaia does not “make” meaning or sense. So, are you referring to the human need to reduce Gaia’s operations to notions of causality or frame it with recognizable domains of meaning making? Is this why you are calling Gaia “an ahuman order” [Clarke 2020, 43]?

BC: Gaia is an ahuman order in that we humans are relatively inconsequential in an ultimate way to the continuation of Gaia. We are not essential to Gaia, and if we succeed in killing ourselves off by trashing our own environment, Gaia will carry on along with whatever biota can still manage the situation.

As we were saying, cognition basically means an ability to sense and respond to one’s environment. Cognition can occur in both living systems, biotic autopoietic systems, and metabiotic autopoietic systems [Clarke 2020, chap. 3]. By metabiotic, I mean a system that does not abandon the biotic domain but rather brings it into a higher-order formation. In the Gaian instance, it means that the Gaian system is, in Lovelock’s words, a “coupled system” integrating the biosphere with the geosphere [Crist and Rinker 2009, 22]. So Gaia is not properly considered simply as a living system. Gaia is not “an organism”; it is not a “superorganism”; it is not “alive” per se. Those ways toward a literal approach to Gaia have mostly been dispensed with. But Gaia as such—as a metabiotic autopoietic system—does produce a kind of planetary sentience by which it carries out its own continuation in relation to its cosmic environment. At the same time, these Gaian operations have meaning for us while having nothing to do with meaning as we experience it. Cognition for us is also part of our metabiotic autopoiesis of conscious experience. Whatever the embodied channel, we cognize in terms of meaning [Clarke 2020, 42–44].

In other words, it’s important not to personify Gaia as a subject or seat of meaning. You could say that the personification of Gaia as an agent producing intentional responses to various provocations is the popular version of the reduction to causality. Lovelock created problems for himself by licensing the use of a mythological name encouraging “random inputs” [Lovelock 2022], such as, Gaia as a revival of the chthonic Earth goddess. Or Gaia has various desires and whims and gets mad when you are bad, and then you get The Revenge of Gaia, which was Lovelock’s book from 2006. All that is culturally fascinating and metaphorically appealing, but Lovelock plays fast and loose with such metaphors and then has to mop up the collateral damage that these figures cause along the way for Gaia’s scientific understanding.

AD: Let’s come to a very important question, especially during the time of the pandemic. Humans and viruses seem to share the same intention of destroying the place they inhabit. If autopoietic Gaia, as you write, continuously observes and selects elements that are “self-bounded” and participates in “meaningful alliances and exchanges” [Clarke 2020, 7] with their environment, what is the credibility of human beings in such a system?

BC: I like the way Margulis thought about this. She placed humans among other organisms, and it’s in the nature of populations of living beings to expand within their environments as far as they can go. Now, in a well-developed self-regulating ecology, biodiversity keeps these processes in a dynamic balance. They are pushed back upon by all their neighbors. None can expand indefinitely. Ecologies go off when this process is impeded, or certain crucial elements to that kind of workable truce or division of niches have gone missing. We know this ourselves, in our own bodies, when overuse of antibiotics degrades our microbiome, and we get sick.

Sagan and Margulis [2007] speak of humans as a pioneer species. In terms of the planetary ecology that has been evolving for eons, we are very recent and still in the process of finding out our limits. These enormous brains allow us to colonize everywhere, but now we are hitting a wall beyond the reach of intelligence. Margulis had this great laboratory image for our situation: say you are a bacterium in a petri dish in this very tasty nutrient substrate giving you everything you need. You think life is great until you hit the edge of the petri dish and you run out of space and nutrients and your happy time is over. Clearly our economic systems are hitting the limits of growth, an idea that was well articulated half a century ago [Meadows et al. 1972]. We know that the goal of capital in the neoliberal economy is to extract profit without limit. We are driven both from below and from above, it would seem, to overpopulate and so demand ever more “resources.” We can see all around us now that these dynamics are now doing untold ecological damage.

If we turn to viruses, as I understand the source of the pandemic, it is likely that COVID-19’s origin is zoonotic. That virus leaped from some other life-form and then caught a ride with humans. Why did this happen? Because human populations are still constantly expanding, we are cutting down the forests, because we are destroying the habitats where these viruses once had a niche that did not previously interact with humans. Ecologically speaking, the mysteries of the virus are still being unfolded. Viruses seem to have emerged early in the evolutionary process. They move genes around. Like bacteria, most viruses are not pathogenic, but some are bad actors. As objects of knowledge, they are in a similar position as bacteria over a hundred years ago. Back then we had to figure out what part bacteria played in relation to the rest of life. For the longest time we just considered them as pathogens to be extirpated. Margulis was an early champion of the probiotic understanding of the planetary integration of what she calls the microcosm with the rest of life, which is for the most part a symbiotic and mutualistic relationship with generalized benefits [see O’Malley 2016; Pradeu 2016].

Microbes are of so many types and kinds because they are under constant mutual coevolution by passing genes back and forth. No mutations necessary. This is called lateral or horizontal gene transfer, and only bacteria and archaea can do it with such promiscuous abandon. And viruses are part of that process as well. What is uncanny is their liminal status in relation to living forms proper. Margulis insists that they are not autopoietic, and so not living beings per se. They are not self-producing; rather, they hijack living systems in order to propagate [1998, 63–64]. So, what does one call that? But nevertheless, the activities and dynamics of the viruses have been part of the planetary ecology for two or three billion years. So, they are completely integrated into Gaia. And that we are freaking out now about pathogenic viruses is part of a larger ecological blowback specific to Anthropocenic conditions. The pandemic is a symptom of human over-expansion and of a willful ignorance about our stress on the planetary ecology. And if we cannot reintegrate ourselves into the planetary ecology in a non-expanding or no-longer constantly expanding way, as Lovelock [2021] has recently suggested, Gaia and its viruses may do it for us by diminishing our numbers. It remains to be seen whether we can get our global sociopolitical act together to avert such “negative feedbacks” drawing down the human presence.

AD: But then, would the Gaian system be majorly affected by the absence of human beings?

BC: Margulis has written that for Gaia, human affairs are merely “petty activities” [Harding 2006, 12]. We are not the engine of life; we are along for the ride like every other life-form. Our demise would bring about some adjustments, especially if our Anthropocene profile as a species were to be suddenly deleted. Other than that, probably nothing major, cosmologically speaking.

AD: In the end, do you take Lovelock’s turn to what he calls “the Novacene,” where cyborgs take control of the human system, or do you support Margulis’s assertion that Gaia will sustain herself through all apocalypses? Lovelock is producing another kind of togetherness, albeit a hierarchical one, where the machines contemplate their own continuation by controlling organic life. What I am also asking is, are both theories predicting the end of humans as we know them, or will there be a different kind of human species?

BC: I placed an article going into Lovelock’s Novacene on Alienocene.com [Clarke 2021b]. This web article goes a little farther than what’s in my book. At the age of one hundred, Lovelock brought out Novacene: The Coming Age of Hyperintelligence. Lovelock’s idea of sentient machines here is no longer Gaia theory. I would call it science fiction in the guise of a speculative philosophy of the singularity. We are now building the intelligent machines that will shortly become self-aware, and gradually, they will take over the planet. Also, for a while they will keep Gaia around, just as we humans would want to do, to keep the planet cool. But eventually a time will come when they will no longer need Gaia’s air-conditioning. Hence, they will let Gaia die off. And then it will be just a silicon planet of intelligent machines. I find that a horrific scenario.

Lovelock suggests that we should be proud to be the progenitors of the next phase of cosmic evolution, in which the hyperintelligent machines will take over from us in the effort to understand the universe. I can’t take this seriously. And if you read it to the end, Gaia dies, leaving an informatic universe for which life is just a passing phase. This is information theory gone completely bonkers. I’ve written on this before [2010, 137– 38] in discussing Stanislaw Lem’s satire on Pirate Pugg in The Cyberiad, a perfect spoof on the informatic idea that Lovelock observes in Novacene. Lem poked hilarious holes in this notion sixty years ago, directly debunking the trends of informatic hyperbole already circulating at the start of the “information age.” This is another reason why you have to stay with Margulis’s reading of Gaia’s dogged toughness.

AD: When you say that “Gaia constructs its own continuation” [Clarke 2020, 43], are we treading the dangerous waters of theology? For example, I remember how Schelling theorized God—as ground which generates its own ground, a kind of self-creation where God wills his own making through an act of grounding.

BC: I think the resonance with these nature-philosophical ruminations of the German philosophers is clear. People have often pointed out that in Kant and other German thinkers of that era we find premonitions of self-reference and autopoiesis. Yuk Hui’s discourse of “cosmotechnics” in Recursivity and Contingency works through this in a really interesting way [on Hui, see Clarke 2021a]. However, the statement you cite is essentially another way of formulating the concept of autopoietic Gaia.

The theory says that an autopoietic system produces its own production; that is a short definition of how autopoiesis works. So, if Gaia is taken as a metabiotic autopoietic system, then one can also say that Gaia is producing its own continuous self-construction. That is all I was going for. Why is this not theology? Theology brings in the concept of a noncontingent or absolute ground, of God as the absolute ground of existence. But in good autopoietic theory, you do not talk about ontological grounds in this way. Systems do not divulge the grounds of being. Systemic forms are essentially groundless, that is, constantly reconstituted. Gaia maintains its own systemic form, which evolves for that very reason, and the ground, such as it is, is simply Gaia’s environment, the material part of the planet which is not Gaia, the mass and material being of the Earth beneath Gaia and the radiation from the Sun above. Gaia is a planetary film or a bubble emerging between the Earth below and the cosmos above, where life on Earth takes its stand.

AD: You have described Gaia as a metabiotic autopoietic system where biotic and abiotic systems couple in a loop. This is a fitting definition of Gaia as derived from neocybernetics. Why was there an inclination in Lovelock and Margulis toward biotic autopoiesis but not for Gaia as metabiotic system forming its own subsystems?

BC: Well, that is an interesting point of divergence between Lovelock and Margulis. The point of my calling Gaia a metabiotic autopoietic system is due to this very coupling of the biological and the geological domains into a meta-system, metabiotic Gaia. It is a hybrid, biogeological system, but the autopoietic element is still driven from the biological affordance of that system. Margulis was the one who, on meeting Maturana and Varela and hanging out with them in the 1980s, really got jazzed by the concept of autopoiesis, and she read autopoiesis in its classical form as a theory of life, as a theory of living form [Varela, Maturana, and Uribe 1974; Thompson 1987]. When she characterizes Gaia, it will be more often in its biotic register. Earlier on she would often refer to Gaia as “the sum of the biota.” That is still a strictly biotic formulation, and later on Lovelock would say no, you need to bring the sum of the biota to the sum of the connected geology. But I think what Margulis could also see was that Lovelock was more willing to demote the biota, and of course his Novacene idea is the ultimate discounting of the biota, an informatic demotion that Margulis would have nothing to do with. So there’s this abiding but also productive tension between their different emphases.

The reason why neither of them got to my idea of a metabiotic synthesis is that neither of them read Niklas Luhmann. I jest, of course, but that is the short answer. Luhmann showed how to take autopoiesis beyond the biotic occasion [as in “The Autopoiesis of Social Systems” (1990) and Social Systems (1995)]. Maturana and Varela did not care for it, but his theory detailed a rigorous and convincing extension of the concept of autopoiesis toward metabiotic occasions, specifically, in describing the distinction but inter-operation of psychic and social systems. But also, his metabiotic extensions of autopoiesis were ultimately constrained to the anthropic arena. He was a sociologist, after all. His social systems theory describes the medium of meaning for human minds and societies. My theoretical move has been to take his metabiotic formulation back to the planetary occasion in order to refine a concept of Gaia that is not fixed to a biotic formulation and so avoids conceptualizing Gaia as alive in its own right, whether as an organism or as a superorganism.

Moreover, as we know, in the place where Gaia is, at and below the surface of the Earth, the geological formations are constantly being decomposed and recomposed as they interact with or are processed through living systems. Take limestone, a ubiquitous and completely biogenic rock built up over eons out of organic detritus [Westbroek 1991, 147–65]. By now, much of the planet’s geology is already postbiotic rather than simply abiotic. After three and a half billion years of life’s churning of the material elements of the planet, we surely live on what Margulis once called “the autopoietic planet” [Margulis and Sagan 2000, 20–24]. To this I just add the further qualifier, metabiotic. The planet’s surface is not living per se. It is not biotic in the manner of cells and organisms, but it has been repeatedly cycled through living processes and redeposited as the environmental ground of the continuation of the system. It is part of the elemental materiality of the Gaian system itself. And this formulation of a metabiotic system forming its own subsystems—that is right out of Luhmann. It is an extraction from social systems theory taken back into Gaia theory, by reversing the line of autopoietic conception [Clarke 2020, 43–44].

AD: We know that second-order or neocybernetics is about the autonomy of self-referential systems. Could you shed some light on Haraway’s moving away from autopoiesis to symbionts and sympoiesis? Do you think this movement is a positive understanding of Gaia?

BC: In Gaian Systems [Clarke 2020, 47–53] I discuss a mid-1990s introduction that Donna Haraway wrote for the Cyborg Handbook, in which the idea of autopoiesis repeatedly comes up [Haraway 1995]. Margulis and Haraway were in touch, and she sent Haraway a preliminary copy of What Is Life?, which was first published in 1995. So, Haraway got an advance look at that manuscript. My takeaway is that Haraway was never really invested in the concept of autopoiesis except insofar as she found it figuring prominently in Margulis’s work, and so for a while she played around with it, before making it a “straw man” concept in her later theoretical polemics [for instance, Haraway 2016, 33].

It seems that the problem is with the “auto” of autopoiesis. The “autonomy of self-referential systems” is shifted to an inappropriate ethical register rather than understood as a description of the recursive self-maintenance involved in the basic integrity of systemic operations. In any event, eventually Haraway hit on sympoiesis to place the emphasis on symbiosis, which is indeed the concept on which Margulis’s greatest importance rests [Margulis 1993, 1998]. Her recovery of the planetary significance of symbiosis, her resurrection and reestablishment of the concept of symbiosis as a fundamental biological and ecological dynamic [see Gilbert et al. 2010], develops right alongside her participation with Lovelock on the elaboration of Gaia. Put another way, for Margulis, Gaia is really the sum of all symbioses. And if we value life in its collectivity, the coming together of life-forms with other life-forms of the same and different kinds, the term sympoiesis is certainly serviceable. Nevertheless, as a concept, it is just a riff, a philosophical riff, a rhetorical gesture. Beyond the initial sketches of Beth Dempster [2000], it is not yet a fully articulated concept like autopoiesis in Maturana and Varela’s Autopoiesis and Cognition, as then submitted to half a century of critical developments [however, see Clarke and Gilbert 2022].

It really comes down to the problem of boundaries. The autopoietic issue forces the question of boundaries [Clarke 2020, 52–53]. An autopoietic system produces and maintains its own boundary as a matter of course as a foundational aspect of its self-production, so you can’t just pontificate that all boundaries are ethically suspect. But as living systems also show us, boundaries are permeable, relative, never absolute. Developmental symbioses show how living systems work with their own and other boundaries, negotiate boundary differences, communicate or cross-cognize across boundaries [Gilbert et al. 2012]. Now the principle of cognition comes back into play. Without the boundary that constitutes the basal integrity of an observing system, starting at the cellular level, there is no cognition. Without a differential between the internal process that cognizes and the environment to be registered, there is no seat for cognition to occupy.

AD: Do you subscribe to Stengers’s argument of Gaia as the Intruder, the transcendental entity as opposed to capitalist transcendence? Is the pandemic evidence of the unpredictability of Gaia and its counter-violence?

BC: Stengers’s text In Catastrophic Times brings out Gaia the Intruder. I read this idea as a cosmopolitical gesture [Clarke 2020, 53–58]. To me, again, Gaia the Intruder is also a philosophical riff, not a scientific statement. But Stengers does not define it by polemical antithesis with another concept. It is a figure of thought by which to wrap our heads around what has been called the “shock of the Anthropocene” [Bonneuil and Fressoz 2017]. Gaia is certainly unpredictable, but still, the COVID pandemic is only a disaster for us, not for Gaia. Its havoc occurs strictly in its disruption of the human order, its playing havoc with our lives, just as our ways of life have also driven other life-forms to extinction. The biopolitical source of the violence is the unbridled expansionism of the neoliberal order—the violence against the biosphere driven by unregulated extraction, and I take that to be the point of Stengers’s argument [see also Ghosh 2021]. Our pioneer species is reaching the limits of its petri dish, and it’s driving us to desperation.

AD: In one of the most provocative chapters in your book, you trace the history of the thinkers of Gaia, right from the cybernetic systems theory of Lovelock, to symbiogenesis and autopoiesis of Margulis, and finally to the anti-systemic actor-network theory of Latour. How have you extracted your own conception of metabiotic Gaia, which is more of a “composite systemic assemblage”?

BC: Gaian Systems presents a systems-theoretical critique of Latour [Clarke 2020, 58–82]. Although I applaud Latour’s interest of Gaia and value his mediations of the concept, I don’t think his actor-network framework is adequate to describe Gaia. One problem is that his efforts to sideline any of the systems descriptions of Gaia fly in the face of the manifestly cybernetic inspirations of Lovelock and autopoietic extensions of Margulis. And stated in autopoietic terms, Latour’s theory lacks operational closure by which the system recurs upon itself to create a unity for that system, by which the system produces its own self-maintaining and cognitive operations, constructing a more regular environment for its own subsystems, which are then ready to consort—sympoietically, if you want—with other systems. For me, actor-network theory is still too atomized. It is certainly about the assembly of collectivities, but what is missing is that final step that actually systematizes the network or the assembly. His networks are open structures of elements lacking that condition of operational closure by which a system achieves systematicity, such that its internal operations are self-producing, and so we’re back to the concept of autopoiesis.

AD: Right. You are also moving away from the kind of philosophizing that would see Gaia itself as a living organism. But then, are you also focusing on how Gaia continuously interacts with species?

BC: For living organisms, Gaia is the environment. It’s a system, but it is a system that produces an environment, because we’re inside it now. And here I agree with Latour completely that we are inside Gaia. We are not above it, as if seeing it from space; we are inside it. And because it produces its own planetary substantiality, it makes it possible for living beings to emerge and live out their lives, all within its “body,” so to speak. Its performance is registered in the maintenance of the habitability of the planet. That is classic Gaia theory. To maintain the planet as habitable is a very grand performance. The conditions of habitability have been held within a very constrained set of parameters, of which temperature is one of the main keys. Gaia is an air-conditioner. Without life our planet would to at least 40 degrees centigrade hotter than it is [Volk 2003, 236–37].

Gaia’s metabiotic merger of the biology and the geology is maintaining the habitability of the climate as the atmosphere itself evolves, as the biosphere altogether evolves. For instance, part of Gaia’s own evolution was to absorb the Great Oxidation Event of 2.2 billion years ago, when the atmosphere rose from trace amounts to its current 20–21 percent oxygen level [Clarke 2020, 240]. Gaia now operates to maintain the complexion of the atmosphere in which a predominantly aerobic biota has evolved, a biota now genetically stamped with the expectation of a world of 20 percent oxygen in the atmosphere. That level has been maintained in a relatively steady state over hundreds of millions of years. That homeostasis is something major that Gaia has been doing. That is a big piece of her performance.

AD: My next questions shift to sociological implications. Whereas organismal boundaries are internally produced primarily as shielding from the external environment, cognition and cognitive boundaries have sociological implications in humans and microorganisms alike.

BC: The crucial thing is that the theory of autopoiesis begins with Maturana and Varela at the biological level and therefore treats the boundary of a living system as a molecular membrane. Life begins by cutting itself out of the environment by producing a membrane, which then becomes a cognitive organ differentiating an inside and an outside. A self-referential process proceeding on the inside of the membrane brings forth a world for that organism. So, as long as you are thinking concretely about living systems, the pertinent boundaries are material, self-produced, made by the system for the system. And in cells, they are made out of molecules.

Now, I don’t think you get a sociology out of Gaia theory. But if you shift to the human situation as treated by social systems theory, you come to the psychic system and the social system as autopoietic in their turn and with their own modalities of self-binding. They perform bounded operations, but the boundaries are no longer material. Autopoietic systems in the human or metabiotic sphere have virtual boundaries. For instance, the operations of the psychic system rest on what is called a reentry of the system–environment distinction into the system [Clarke 2014, 94–96]. Virtual boundaries are porous to environmental states, of course, but even so, that form of distinction is the condition of having a stable self-production. Cognitive boundaries are created by the processing of distinctions and, to begin with, in the human mind, by the internalizing of the distinction between system and environment.

AD: Do we have anything to learn from the microbes on the ethical plane?

BC: It remains an intriguing question, what human societies can learn from the lifeways of microorganisms. In a healthy ecosystem, a biodiverse jostling arrives at a kind of mutual distribution of viable elements. Margulis links these points to the ethical plane. What we can learn from the microbes is planetary recycling [Margulis 1998, 105–6, 119–21]. That is how they live, by forming colonies of diverse kinds, in which one kind lives on and so recycles the waste of another kind. No organism can live on its own waste; Margulis constantly makes that basic metabolic point. Your own organic wastes must be flushed away, and for that you need a medium, you need an environment that can absorb and disperse that influx. But these bacterial colonies form layers with distributed functions. And as a mutualistic, symbiotic Gaian consortium, they are recycling each other’s waste and the whole community benefits by maintaining its own local conditions of continuation.

AD: Autopoiesis is concerned with self-maintenance and not directly with reproduction over generations. Could you explicate this phrase a little more, that autopoietic Gaia is a “self-producing but a nonreproducing entity” [Clarke 2020, 165]?

BC: I am simply glossing Margulis when I say Gaia is self-producing but not reproducing—it is not giving birth to a baby Gaia. Let’s consider the neo-Darwinist critique of Gaia that emerged from a guy like Richard Dawkins [1982] back in the 1980s. Evolutionary dynamics were to be due entirely to processes of natural selection, and these demand a population of individuals that can then differentially survive or not survive. So then, because Gaia is a population of one, there is no way that it can be part of a natural-selective process. This issue takes us back to the original presentation of autopoiesis as a challenge to mainstream biology, evolutionary thinking that was totally oriented toward heteronormative reproduction.

Maturana and Varela introduced autopoiesis to make the point that no organism even survives to have a chance to reproduce unless it maintains its own life in the first place, in the face of continuous environmental challenges. Autopoiesis gave a name to the principle of the self-maintenance of a living system regardless of its reproductive status [see also Bich and Etxeberria 2013]. When Margulis took up autopoiesis into her own biological thinking, it was as part of her campaign to contest the neo-Darwinist overemphasis on the differential survival of reproducers. Her reception of autopoiesis also reinforced her conviction that in the vast range of its manifestations, symbiosis, too, is only secondarily concerned with reproduction. Symbiosis is more fundamentally a matter of intimately shared environments, as different organisms find they make a better living when in persistent bodily contact.

For instance, we have Margulis in particular to thank for the rising profile of this important new idea of the holobiont—the living system as expanded to include all the life-forms that combine in the making and maintenance of a no longer strictly “individual” plant or animal [Chiu and Gilbert 2015; Gilbert and Tauber 2016; Clarke 2020, 235–40]. Our own status as holobionts begins when the newborn comes down the mother’s birth canal and picks up her bacterial complement, a starter kit for its own nascent microbiome. Here, the microbiome is “inherited,” but not genetically, rather, environmentally, or epigenetically. But all these vital symbiotic dynamics were once pushed to the margins of biology because they did not have to do strictly with the survival of the fittest through reproductive fitness and all that stuff. And that is also why it is not, properly considered, a planetary “organism,” because living organisms do have to reproduce to maintain the generation of their lines. But Gaia does not really produce a second Gaia; it just persists and evolves. Both Lovelock and Margulis are happy with the idea that biological evolution is an elemental phenomenon within the evolution of Gaia at large. As the microcosm evolves, as species evolve, Gaia evolves—there is a massive planetary feedback loop here operating over evolutionary time. And all the while, there is innovation, inevitable change. This is basic systems theory: despite a common mischaracterization, autopoietic systems cannot merely replicate themselves in perpetuity. This is because they are foundationally embedded in the changes they make to their own environments, which then feed back incrementally upon the system.

AD: As you write toward the end of Gaian Systems, “The immune system’s primary concern is not to search out and destroy anything labeled as non-self, but rather to hold together the many selves of the holobiotic ecosystem, composed of the animal host coupled to its own microbiome, by identifying, tolerating, and recruiting beneficial microbial symbionts” [Clarke 2020, 238]. Would you agree with Varela’s reading of our immunological responses as Gaia acting inside our bodies?

BC: You are referring to chapter 8 of Gaian Systems where I discuss an article by Varela and Anspach [1991], which brings Gaia discourse into Varela’s immunological thinking. In this paper he grants the facticity of Gaia while using it as a kind of ecological metaphor in his effort to change our ideas about the immune system. That is, he pursues a kind of Gaian allegory built on this chiasmus: if we are inside Gaia, then Gaia is also inside us. Varela’s figure illustrates what we now recognize as the new immunological understanding of the holobiont and its microbiome. In this reconception, the immune system not only marshals a militia of antibodies on the prowl to snuff out any invaders from the outside world. Equally consequentially, the immune system recruits microbes from the environment for the microbiome and operates on its behalf to preserve a healthy internal ecology [see Gilbert, Sapp, and Tauber 2012]. It is not that Gaia is literally “in us,” although there is some sense to that idea; it is rather that the symbiotic operations of the immune system on behalf of the holobiont is a microcosm of what Gaia does for life on the planet. There is a comparable scene of mutualistic collectivity in the service of “habitable conditions.”

AD: But if, as you write, “only the occasional bad microbial actors are targeted for removal” [Clarke 2020, 238], and this is true for all holobionts, with regards to the ongoing pandemic, where do you think we are failing?

BC: Let us anticipate that Gaia will sort things out, and the effect of its own persistence will be the maintenance of habitability for some revised or evolved version of the planet’s biota. But habitability is still a precarious situation. It does not mean that life is easy; it just means that it is possible. Here is your condition of habitability: now you figure out how to live in a manner that doesn’t do you in before your time. That is Gaia’s bottom line. If we don’t get a handle on anthropogenic global warming, civilization is in real peril. Something will survive, presumably. What Lovelock expects to happen is that, after the current tipping points have been surpassed, Gaia will reset into an altered regime, because its systemic elements and operations will now have shifted to a depleted condition relative to the current biota. In all likelihood, its homeostasis will reset at a hotter point and some suite of life-forms will be able to hack it. In other words, Gaia is not coming to the rescue. While there’s still time, we need to work it out for ourselves. We need to get right with today’s Gaia, because otherwise, tomorrow’s Gaia will not be habitable for us. In sum, we could approach Gaia as a way to conceive what is being asked of us with regard to our own preservation as a species and as a civilization.

AD: To say it more bluntly, what I meant was that humans were the only holobionts that are failing, depleting themselves.

BC: Yes, and we are also destroying the habitats of many of our relatives, as indigenous peoples often say, and we moderns are at fault for that. Let us human beings rather become Gaian beings integrated into the planetary panorama, protective of the biodiversity in which we participate. We have our being as part of an ahuman order, beholden to gifts we have done nothing to deserve. Now we have to earn our keep.

Bruce Clarke is Paul Whitfield Horn Distinguished Professor of Literature and Science in the Department of English at Texas Tech University. He was Baruch S. Blumberg/NASA Chair in Astrobiology at the Library of Congress in 2019; Senior Fellow at the Center for Literature and the Natural Sciences, Friedrich Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg in 2015; and Senior Fellow at the International Research Institute for Cultural Technologies and Media Philosophy, Bauhaus-University Weimar in 2010–11. His latest books are Writing Gaia: The Scientific Correspondence of James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis, coedited with Sébastien Dutreuil (2022), and Gaian Systems: Lynn Margulis, Neocybernetics, and the End of the Anthropocene (2020); other books include Neocybernetics and Narrative (2014), Posthuman Metamorphosis: Narrative and Systems (2008), and Energy Forms: Allegory and Science in the Era of Classical Thermodynamics (2001). He coedits the book series Meaning Systems, published by Fordham University Press, and is the editor or coeditor of seven essay collections, most recently Posthuman Biopolitics: The Science Fiction of Joan Slonczewski (2020) and, with Manuela Rossini, The Cambridge Companion to Literature and the Posthuman (2017).

Asijit Datta is currently working as Assistant Professor (II) in the Department of Liberal Arts at SRM University (Andhra Pradesh, India). He is also employed as assistant editor at the Journal of Posthumanism (Transnational Press, London). He has previously taught at Presidency University, Vidyasagar University, Ramakrishna Mission, Narendrapur, and Bethune College. He completed his MA in English from Presidency College in 2009 and received his PhD from the Department of Film Studies, Jadavpur University, in 2017. His academic interests pertain to posthumanism, Beckett studies, modern European theater, world cinema, and psychoanalysis.

Acknowledgement

Bruce Clarke would like to thank Asijit Datta for setting up the interview and its transcription and to join Professor Datta in thanking Patrali Chatterjee for her assistance in transcribing the interview on which this article is based.

References

Arènes, Alexandra, Bruno Latour, and Jérôme Gaillardet. “Giving Depth to the Surface: An Exercise in the Gaia-graphy of Critical Zones.” The Anthropocene Review 5.2 (2018): 120–135.

Barlow, Connie, and Tyler Volk. “Open Systems Living in a Closed Biosphere: A New Paradox for the Gaia Debate.” BioSystems 23.4 (1990): 371–84.

Bich, Leonardo, and Arantza Etxeberria. “Autopoietic Systems.” Encyclopedia of Systems Biology. Ed. Werner Dutzky et al. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2013. 2110–13.

Bonneuil, Christophe, and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz. The Shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, History and Us. Trans. David Fernbach. London: Verso, 2017.

Chiu, Lynn, and Scott F. Gilbert. “The Birth of the Holobiont: Multi-species Birthing through Mutual Scaffolding and Niche Construction.” Biosemiotics 8 (2015): 191–210.

Clarke, Bruce. “Communication.” Critical Terms for Media Studies. Ed. W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2010, 131–44.

———. “Cybernetics, Intelligence, and Cosmotechnics: Catherine Malabou’s Morphing Intelligence and Yuk Hui’s Recursivity and Contingency.” American Book Review 42.1 (Spring 2021a): 12–14.

———. Gaian Systems: Lynn Margulis, Neocybernetics, and the End of the Anthropocene.

Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2020.

———. “Lynn Margulis, Autopoietic Gaia, and the Novacene.” Alienocene 7 (June 2021b). https://alienocene.com/2020/06/07/lynn-margulis-autopoietic-gaia-and-the-novacene.

———. Neocybernetics and Narrative. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2014.

Clarke, Bruce, and Sébastien Dutreuil, eds. Writing Gaia: The Scientific Correspondence

of James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2022.

Clarke, Bruce, and Scott F. Gilbert. “Margulis, Autopoiesis, Sympoiesis.” Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere. Ed. Caroline A. Jones, Natalie Bell, and Selby Nimrod. Boston: List Visual Art Center, MIT, 2022. 63–78.

Crist, Eileen, and H. Bruce Rinker, eds. Gaia in Turmoil: Climate Change, Biodepletion, and Earth Ethics in an Age of Crisis. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009.

Dawkins, Richard. The Extended Phenotype: The Long Reach of the Gene. Oxford UP, 1982. Dempster, Beth. “Sympoietic and Autopoietic Systems: A New Distinction for Self-

Organizing Systems” (2000). Available at semanticscholar.org.

Ghosh, Amitav. The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2021.

Gilbert, Scott F., Emily McDonald, Nicole Boyle, Nicholas Buttino, Lin Gyi, Mark Mai, Neelakantan Prakash, and James Robinson. “Symbiosis as a Source of Selectable Epigenetic Variation: Taking the Heat for the Big Guy.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 365 (2010): 671–78.

Gilbert, Scott F., Jan Sapp, and Alfred I. Tauber. “A Symbiotic View of Life: We Have Never Been Individuals.” The Quarterly Review of Biology 87.4 (December 2012): 325–41.

Gilbert, Scott F., and Alfred I. Tauber. “Rethinking Individuality: The Dialectics of the Holobiont.” Biology and Philosophy 31 (2016): 839–53.

Haraway, Donna J. “Cyborgs and Symbionts: Living Together in the New World Order.” The Cyborg Handbook. Ed. Chris Hables Gray with Steven Mentor and Heidi J. Figueroa-Sarriera. New York: Routledge, 1995. xi–xx.

———. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2016.

Harding, Stephan. Animate Earth: Science, Intuition, and Gaia. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2006.

Hui, Yuk. Recursivity and Contingency. New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2019.

Latour, Bruno. Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime. Trans. Catherine Porter. Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2017.

Lem, Stanislaw. The Cyberiad: Fables for the Cybernetic Age. Trans. Michael Kandel.

1965; New York: Harvest, 1985.

Lovelock, James E. The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth. New York: Norton, 1988.

———. “Beware: Gaia May Destroy Humans before We Destroy the Earth.” The Guardian, November 2, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/ 2021/nov/02/beware-gaia-theory-climate-crisis-earth.

———. Letter to Lynn Margulis, November 5, 1981. In Clarke and Dutreuil 2022, 202–3.

———. “Our Sustainable Retreat.” Crist and Rinker 2009, 21–24.

———. The Revenge of Gaia: Earth’s Climate in Crisis and the Fate of Humanity. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

Lovelock, James E., with Bryan Appleyard. Novacene: The Coming Age of Hyperintelligence. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2019.

Luhmann, Niklas. “The Autopoiesis of Social Systems.” Essays on Self-Reference. New York: Columbia UP, 1990, 1–20.

———. Social Systems. Trans. John Bednarz Jr. with Dirk Baecker. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1995.

Margulis, Lynn. “Big Trouble in Biology: Physiological Autopoiesis versus Mechanistic Neo-Darwinism” (1990). Margulis and Sagan 1997, 265–82.

———. “Foreword.” Harding 2006, 7–12.

———. Symbiosis in Cell Evolution: Microbial Communities in the Archean and Proterozoic Eons. 2nd ed. New York: W. H. Freeman, 1993.

———. Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution. New York: Basic Books, 1998. Margulis, Lynn, and Dorion Sagan. Dazzle Gradually: Reflections on the Nature of

Nature. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2007.

———. Slanted Truths: Essays on Gaia, Symbiosis, and Evolution. New York: Copernicus, 1997.

———. What Is Life? Berkeley: U of California P, 2000.

Maturana, Humberto, and Francisco J. Varela. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. Boston: Riedel, 1980.

Meadows, Donella H., Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books, 1972.

O’Malley, Maureen A. “The Ecological Virus.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 59 (2016): 71–79.

Pradeu, Thomas. “Mutualistic Viruses and the Heteronomy of Life.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 59 (2016): 80–88.

Sagan, Dorion, and Lynn Margulis. “Welcome to the Machine.” Margulis and Sagan 2007, 76–88.

Schwartzman, David W., and Tyler Volk. “Biotic Enhancement of Weathering and the Habitability of Earth.” Nature 340 (August 10, 1989): 457–60.

Sleep, Norman H., Dennis K. Bird, and Emily Pope. “Paleontology of Earth’s Mantle.” Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 40 (2012): 277–300.

Stengers, Isabelle. In Catastrophic Times: Resisting the Coming Barbarism. Trans. Andrew Goffey. Ann Arbor: Open Humanities P, 2015.

Stolz, John F. “Gaia and Her Microbiome.” FEMS Microbiology Ecology 93.2 (2017): 1–13.

Thompson, William Irwin, ed. Gaia, A Way of Knowing: Political Implications of the New Biology. Great Barrington, MA: Lindisfarne Press, 1987.

———, ed. Gaia 2, Emergence: The New Science of Becoming. Hudson, NY: Lindisfarne Press, 1991.

Varela, Francisco J., and Mark Anspach. “Immu-knowledge: The Process of Somatic Individuation.” Thompson 1991, 68–85.

Varela, Francisco J., Humberto M. Maturana, and Ricardo Uribe. “Autopoiesis: The Organization of Living Systems, Its Characterization and a Model.” BioSystems 5 (1974): 187–96.

Volk, Tyler. Gaia’s Body: Toward a Physiology of Earth. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003. Westbroek, Peter. Life as a Geological Force: Dynamics of the Earth. New York: Norton. 1991.

Westbroek, Peter, and Elisabeth W. De Jong, eds. Biomineralization and Biological Metal Accumulation: Biological and Geological Perspectives. Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 1983.

symploke, Volume 30, Numbers 1-2, 2022, pp. 431-451 (Article)

Published by University of Nebraska Press

For additional information about this article

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/885955

Member discussion