CCI 1.1. Introduction to the Cybernetic Countercultures Intensive: In Search of Organic Cybernetics

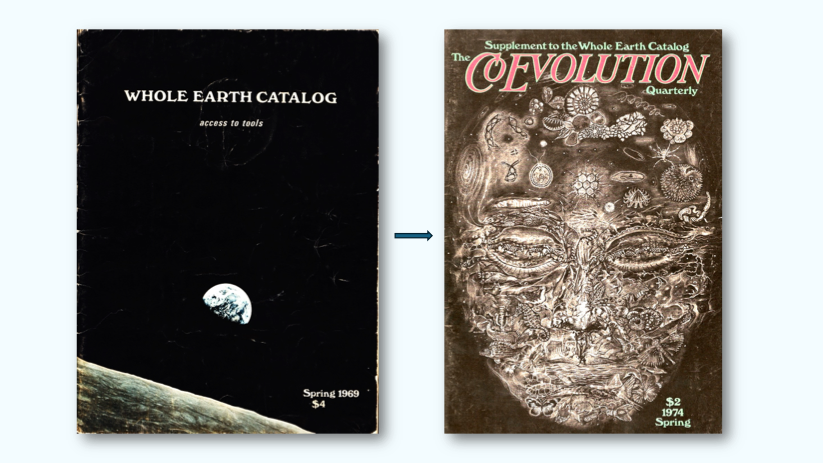

Twenty years ago, as a mid-career scholar of literature and science, I began an immersion into the Whole Earth Catalog and CoEvolution Quarterly—an immersion into the systems theme in their content as well as their fascinating editorial backstories—material for a kind of nonfiction literary history. I had missed the Catalog when it first appeared, in 1968, the year I graduated from high school in McLean, VA, just outside DC, and then entered Columbia University in NYC. So I was East Coast born and bred, and only later came across a copy of the Last Whole Earth Catalog, on my girlfriend’s bookshelf. Of CQ I knew nothing at all until I turned back to the Catalog around 2005, this time eager to study it as an important source for the popular dissemination of cybernetics in the later 20th century. There it was in every issue, the opening section, “Understanding Whole Systems.” The Earthrise photograph taken on Christmas Eve from Apollo 8’s transit over the lunar landscape graced the cover of the Spring 1969 number. Here it was: the Earth itself is the whole system par excellence. With ecological consciousness supercharged by space technology at the leading edge of the 1960’s and 1970’s communalist counterculture and green intelligentsia, Stewart Brand invented the Catalog and carried CQ forward, a vehicle to provide his extended community with access to tools. Cybernetics—a specific discipline for the study of systems, biological and technological—was on the menu.

Where the history of cybernetics is concerned, the Whole Earth Catalog and CoEvolution Quarterly are the premier publications of the American counterculture. Early on in this research project I received the private donation of a nearly full set of CoEvolution Quarterlies and Whole Earth Reviews—the nucleus of my own Whole Earth archive. I trolled the Internet and purchased various iterations of the Whole Earth Catalog proper. Thanks to Barry Threw and Gray Area, the online Whole Earth Index puts almost the entire run of these publications at one’s digital fingertips. I invite you to browse this resource throughout our Intensive.

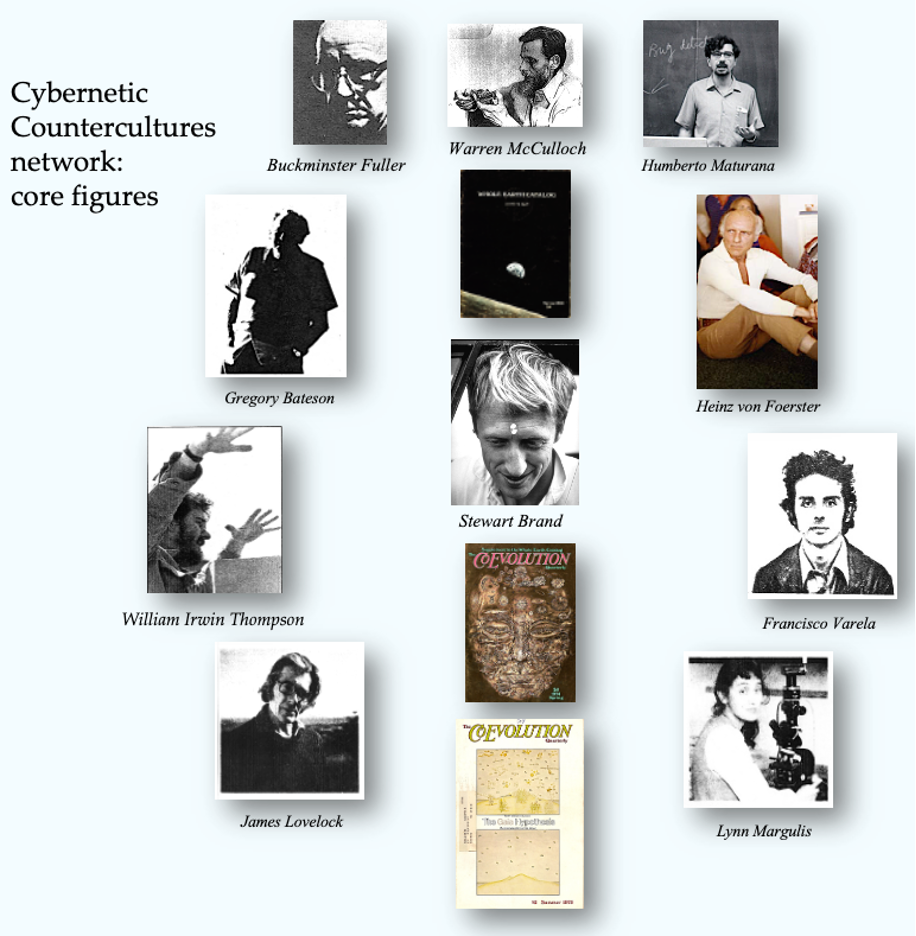

Pictured is the first echelon of the Cybernetic Countercultures network: scientists and engineers gathered in by writers and cultural observers whose mutually resonant efforts expanded the repertoire of cybernetics writ large, bringing it into a phase of thought variously called second-order cybernetics, or neocybernetics for short, and for which the understanding of living systems was paramount. What especially sets the Cybernetic Countercultures apart from the cybernetic mainstream is its devotion to doing cybernetics in a biological, organismal key.

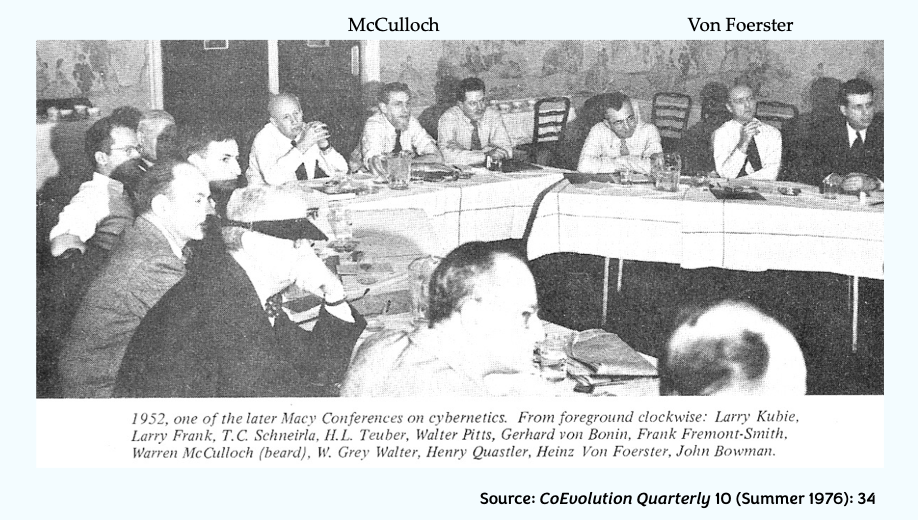

The Cybernetic Countercultures diagram adds other key names and a selection of key texts. Each line traces the thread of a story about a personal and/or intellectual relationship. For instance, picking up the larger story with the Macy Conferences on Cybernetics, neurophysiologist Warren McCulloch was at their intellectual center, as seen here, at the center of the lead table. These ten meetings running from 1946-1953 laid down complex foundations for numerous strands of cybernetic development. Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead were present at a number of these meetings, as was Heinz von Foerster once he arrived in the States in 1949.

McCulloch was instrumental in bringing von Foerster to the University of Illinois where he would set up the Biological Computer Lab in 1958. Over the next two decades, von Foerster created a major hub of cybernetic research activities. By the end of the 1960’s, it had become a radical incubator for neocybernetics—the second-order turn toward organic systems in their crucial distinctions of form and purpose.

Next in line, Stewart Brand was a second-generation beneficiary of the cybernetic tide for which McCulloch and von Foerster were key fountainheads. From the inception of the Whole Earth publications, its “Understanding Whole Systems” section foregrounded salient lines of cybernetic thinking with reviews of pertinent texts, such as notices of Norbert Wiener and W. Ross Ashby in the inaugural number of the Catalog. Brand cites the idiosyncratic systems thinker Buckminster Fuller as the leading inspiration for the global outlook of the Whole Earth sensibility. Fuller’s parallel conception of “Spaceship Earth” was launched in the control-and- communication spirit of the first cybernetics. Listed in the Whole Earth Catalog, Fuller’s curriculum for design science in 1969’s Utopia or Oblivion included general systems theory, cybernetics, and communications.

However, by 1974, as announced in the Whole Earth Epilog and continuing throughout the ten-yar run of CoEvolution Quarterly, Gregory Bateson became the leading luminary of the Whole Earth network. By this time Bateson himself had channeled the later harvest of his multifarious professional wanderings—as a zoologist and natural historian, as a cultural anthropologist, Macy Conference participant, social cyberneticist, psychotherapist, resident ethnologist at the Palo Alto VA hospital, and director of dolphin research labs at both John Lilly’s Communication Research Institute on St. Thomas and the Oceanic Institute on Oahu, Hawaii—into the tableau of environmental and systemic intuitions gathered in Steps to an Ecology of Mind in 1972.

In his headnote to the Whole Earth Epilog, Brand explained that with the release of Steps, through Bateson, “I became convinced that much more of whole systems could be understood than I thought, and that much more existed wholesomely beyond understanding than I thought—that mysticism, mood, ignorance, and paradox could be rigorous, for instance, and that the most potent tool for grasping these essences—these influence nets—is cybernetics.” Here was whole-systems discourse taken to a new level of coherence, breadth of application, and topical relevance for the psychedelic intelligentsia of Brand’s community.

As a warm-up exercise during the three-year hiatus between the end of the first run of the Whole Earth Catalog in 1971 and the debut of CoEvolution Quarterly in 1974, Brand publishes II Cybernetic Frontiers, a monograph compiling two sizable magazine articles. One tackles a signal moment in machine cybernetics, the dawn of video games—specifically, the primeval game Space Wars, then being played by the “Computer Bums” at Stanford late at night on idle mainframes. But the lead article, “Both Sides of the Necessary Paradox,” marks Brand’s extensive initial report on Gregory Bateson’s arrival within the Cybernetic Countercultures.

And in a coda to that Bateson chapter, in line with an announcement of the imminent launch of CoEvolution Quarterly, in a kind of throwaway remark or significant hesitation, Brand hits upon an apt formula: “As a Bateson enthusiast and a publisher I’ll be printing sundry papers, speculation, gossip, tidbits, letters, etc. on cybernetics (well, organic cybernetics), in the periodic supplement to the revived Whole Earth Catalog.” This interpolated phrasing, I think, adds the vital difference that distinguishes the conceptual core of the Cybernetic Countercultures—their interrelated modes of adherence to the spirit of organic cybernetics. I read this parenthetical moment in Brand’s text, presided over by the profound groundedness and good nature of Bateson’s mature discourse, as an inadvertent declaration, an admission of the priority of living systems proper to Brand’s Whole Earth project. And that was so even under the looming shadow of a nascent cyberculture under Brand’s vanguard journalistic observation, already depriving the Computer Bums of regular sleep schedules.

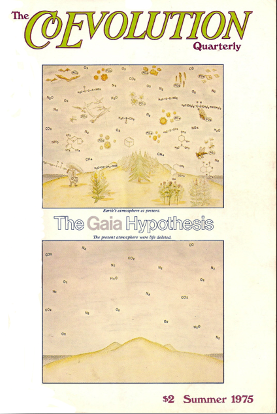

Some may be wondering what Margulis and Lovelock, the co-inventors of the Gaia hypothesis, this microbiologist from Massachusetts and atmospheric chemist from England, are doing here as part of the Cybernetic Countercultures. In fact, they are card-carrying members of the Whole Earth network @ 1975. Brand issued their credentials that summer when CoEvolution Quarterly published the first article on the Gaia hypothesis to appear in a non-scientific journal. We will have plenty to say about their cybernetic approaches to Gaia as both science and philosophy.

The Chilean neuroscientist Humberto Maturana worked with McCulloch during a stint at MIT in the early 1960s, where they were co-authors of the famous paper “What the Frog’s Eye Tell the Frog’s Brain.” This neurological study of animal vision showed experimentally that the frog’s sensory apparatus did not just furnish it with a neutral copy of its environment. Instead, as we can now phrase the matter, it generated its Umwelt—the world as attuned by its cognitive apparatus to its maintenance in being. And the Umwelt of the frog turned out to be one in which quickly moving peripheral specks were preferentially frontloaded to its attention, as these were likely to be the flies on which it depended for a meal, the better to snag them with its long tongue, like a retractable missile hitting its target. This cybernetic line of experimental epistemology runs directly from McCulloch to Maturana and his friend, collaborator, and frequent sponsor at the BCL, Heinz von Foerster.

In an interview conducted in 1998, Maturana underscores biological cognition as the central concern of his own research carried forward at the BCL. Asked what he may have contributed to von Foerster’s thinking, he remarks that he

came in a moment to the BCL in which my way of facing the questions about cognition in the domain of biology made a difference: introducing the observer as an active participant in the generation of understanding and in the process of explaining the observer. That was my concern: explaining the observer, not merely claiming, the observer is there, but explaining it.

Maturana goes on to recollect what he took to be a watershed moment in his interactions with the BCL, crossing a conceptual threshold from an earlier control-theoretical informational cybernetics to the cognitive reformation von Foerster will later name second-order cybernetics:

When I came back in 1968 for a longer time… I put my emphasis on circularity, on the observer participating, on the distinction by an observer… [Von Foerster] was still speaking in those days about information and information in the environment. I remember that during one of my first lectures in Illinois I said: ‘Information does not exist, it is a useless notion in biology… because biological systems do not operate in these terms, it is a useful notion for design for understanding systems that are very well specified, you may describe relations in these terms but living systems do not operate in those terms.

At that moment in the late 1960s, Maturana’s biology of cognition helped to drive the formation of a newer cybernetics discontented with models borrowed from information theory that treated sensory experience according to diagrams of telephonic apparatuses. The BCL was ready to approach a constructivist reformulation of cognition. Von Foerster’s own cognitive turn reaches full statement and maximum compression in the final remarks of his paper “Thoughts and Notes on Cognition,” first published in 1970 alongside Maturana’s “Neurophysiology of Cognition” (1970). Here von Foerster directly rejects his prior formulation—the one Maturana recalled in his interview regarding “information in the environment”—and revokes the ontological credentials of the information concept. Information here is no longer the freestanding transmitted input to a receiving apparatus – a neuron or whatever – but an output internally generated by self-referential cognitive processes. As with messages from the frog’s eye as constructed by the frog’s brain—but now, generalized to biological cognition at large. Von Foerster’s paper ends:

5.6 Cognitive processes create descriptions of, that is information, about the environment.

6 The environment contains no information. The environment is as it is.

In other words, in these early stirrings of neocybernetic formulations, information is no longer granted system-external circulation. Rather, it becomes the system-internal outcome of a cognitive loop, which process may then go on to attribute its construction to a source in its environment. Such processes of biological cognition are at the base of neocybernetics’ epistemological constructivism. And if this reversal of cognitive attitude is somewhat less of a radical gesture in the present moment, nonetheless, it remains a stark departure from objectivistic truisms. But in 1970, at the BCL and out on the West Coast, it was a non-stop ticket departing the scientific mainstream for the cybernetic counterculture.

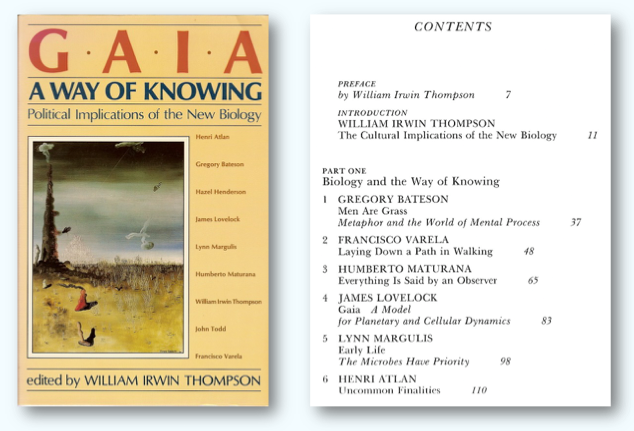

Returning to our diagram, when read down the center as a narrative sequence, it makes a passage through William Irwin Thompson and his Lindisfarne Association, acknowledging their role in the wider cultivation of neocybernetics and Gaian discourse. Begun in the early 1970s as an intentional community and so intrinsically in the audience for the Catalog’s continuation in CQ, Lindisfarne was a private salon that, through direct connections with Brand’s Whole Earth network, tapped into the Cybernetic Counterculture’s embrace of Bateson’s late work, into the biological cybernetics of Maturana and Varela, and into the planetary cybernetics of Margulis and Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis. Here for the record, in one splendid compendium drawn from a meeting held in 1981, Gaia: A Way of Knowing—Political Implications of the New Biology, is a certain crest of the “organic cybernetics” celebrated by CoEvolution Quarterly. Developing the autopoietic and cognitive lines of approach between life and mind, Thompson’s “new biology” is another phase in that exploration.

To round out the Cybernetic Countercultures roster, we turn to Humberto Maturana’s most gifted student and the co-author of the concept of autopoiesis, Francisco Varela. Suffice it to say here that the concept of autopoiesis was the epitome of the organic cybernetics of that moment. It was precisely a theory about the operational form of living systems, which are auto-poietic insofar as they are the ongoing products of their own incessantly maintained production. Unlike machines—at least in theory—living systems are burdened with self-maintenance; their being is inherently precarious. As we will discuss next week, autopoiesis defines a class of systems that can both generate and pursue intrinsic goals.

Let’s tune in on particular episode of support for Varela extended by von Foerster just as the BCL is closing up shop in 1975. Among the many generous actions von Foerster took to help launch Varela’s expatriate scientific career after his forced departure from Pinochet’s Chile was to introduce him to Brand’s Whole Earth network. Now, the von Foerster archive has a copy of a letter from Varela to Brand, responding to Brand’s invitation to comment on “Sagan’s Conjecture” for potential publication in CoEvolution Quarterly. Let us dig in here for a moment, as this episode nicely illustrates the collegial workings of the Cybernetic Countercultures. “Sagan’s Conjecture” first appeared in the same Summer 1975 number with Margulis and Lovelock’s “The Atmosphere as Circulatory System of the Biosphere: The Gaia Hypothesis” as the featured article. We see one of Brand’s standard editorial techniques, generating curated copy for the magazine by inviting multiple responses to a provocative question or issue. He explains at the outset: “One intended function of The CQ is to be a conversation pit for cooked and half-cooked cybernetic ideas.” Sagan’s Conjecture followed:

If the energy-per-pulse flowing through and interacting with a system is greater than the binding energy of the least strongly bound component of the system, then there will be a net loss of order in the system. Conversely, if the pulse energy is less than that of the weakest bond, there will be a net gain of order in the system.

Brand’s set-up for this material-energetic thesis makes it clear that Sagan meant the dynamics it describes to account for the negentropic dynamics of biological systems—their ability to build up increasingly complex organization in the face of the physical rule of entropy—while operating in a through-put linear fashion strictly on thermodynamic principles of energy flow.

What then did members of the Cybernetic Countercultures have to say about “Sagan’s conjecture”? Brand reports that “Gregory Bateson was unthrilled by Sagan’s Conjecture. He distrusted its ambition to span too many levels of organization. ‘Suppose you have a family or something—a group of people who trust each other. Then you introduce the assertion that one of them is a spy. Does Sagan explain the net loss of order in the group?’” Bateson’s reported remarks elegantly parry Sagan’s thrust. He simply restates Sagan’s idiom of systemic “bonds” as referring not to physicochemical affinities but to social ties, bonds of kin. The implication is that the degree of social “order” in a family system or, say, in an animal community, may be measured by the level of mutual trust in behavioral evidence there. Bateson’s family-therapy counter-example sorely deflates Sagan’s bid for universal or cosmic application.

Be that as it may, Brand persisted a bit longer in his interrogations on the matter. Presumably due to von Foerster’s boosting of his young protégé, Brand appears to have offered Varela a shot at the Sagan question. Varela’s reply, dated September 11, 1975, would indicate that a relation of some familiarity already existed between them: “Dear Stewart: I would like to accept your invitation to comment . . . .” Varela then states his thesis clearly: “what I see as fundamentally wrong here is that both the notion of order and the notion of energy are strictly observer bound and here they are treated as entities in themselves irrespective of the observer’s framework. This is very misleading. Let me expand on this. . . .” Varela goes on to type out two packed single-spaced pages of classic second-order cybernetic rebuttal of the Conjecture. Two months later, by which time apparently Brand had demurred on its publication, Varela sends a copy of this letter to Heinz, who exercises superb professorial discretion in his own reply: “Thanks also for letting me see your letter to Stewart Brand. We, at the BCL, humbly submit to you that you withdraw this letter. We suggest that you read it again with some distance from the time of writing, and by doing so we know that you will know why we make this recommendation.” Heinz delicately intimates that the treatise Francisco contributed to that CoEvolution Quarterly conversation was altogether too prolix and pedantic for the occasion. However, he did not mention what his archive appears to show, that he had drafted his own invited response to Sagan’s conjecture but abandoned it unsent.

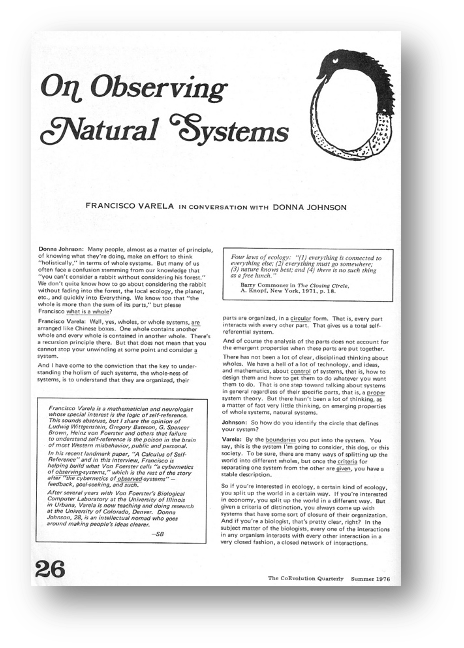

In any event, in a short postscript to his over-lengthy letter to Brand, Varela also mentioned, “I am enclosing a copy of some ideas on the living organization, which I thought you might enjoy.” Quite likely this was his recently-released, lean and lead-authored paper “Autopoiesis: The Organization of Living Systems,” directly vetted by von Foerster for publication in BioSystems the year before. If so, Brand would have in hand all he needed to know about the brilliance and proper métier of his new correspondent. But whatever the case, the Summer 1976 number of CoEvolution Quarterly features a lengthy and quite superb interview with Varela, “On Observing Natural Systems.” Brand’s headnote introducing this virtually unknown but charismatic and creative neuroscientist to the larger CoEvolution Quarterly audience places Varela squarely within the inner circle of the Cybernetic Countercultures: “Francisco Varela is a mathematician and neurologist whose special interest is the logic of self-reference. This sounds abstruse, but I share the opinion of Ludwig Wittgenstein, Gregory Bateson, G. Spencer Brown, Heinz von Foerster and others that failure to understand self-reference is the poison in the brain of most Western misbehavior, public and personal.” For good measure, Brand also exercises his editorial prerogative in lifting von Foerster’s Ouroboros from the 1974 BCL volume Cybernetics of Cybernetics and appending it to the Varela interview, I take it, as a marker of conceptual continuity. Heinz himself had lifted that emblem of self-referential recursion—the logo of second-order cybernetics—from a publication by the developmental biologist C. H. Waddington. Cybernetics of Cybernetics was a massive student production von Foerster financed with $10,000 from Brand’s Point Foundation, which distributed the profits of the Last Whole Earth Catalog. So you see, it all hangs together!

I hope our first spin through the Cybernetic Countercultures network has justified naming this diverse band of systems thinkers countercultural. It is not just that they all consorted with Stewart Brand and the Whole Earth network. What’s most important is what their conceptual orientations have in common: they all lay consistent, often insistent cybernetic emphasis on living systems. As a gathering, they bring a coherent set of physiological, biological, and ecological approaches to issues of cognitive and communicational operation. Throughout the Cybernetic Countercultures literature, these themes parallel but also contrast with the abiotic points of view extended from idealizations or realizations of physical and mechanical systems.

We can conclude this introduction with a brief glance at Heinz von Foerster’s CoEvolution Quarterly review of Brand’s II Cybernetic Frontiers. This episode brings the logic of the crucial contrast between organic and machine cybernetics into focus. To garner a sympathetic review of his own book within his own magazine, Brand reached out to the affable and very quotable Heinz, who wrote: “To know more about cybernetics from a man who helped in giving birth to this baby a quarter century ago was one of Brand’s motivations to see Bateson in the first place. He recalled Bateson’s statement in Steps to an Ecology of Mind: ‘I think that cybernetics is the biggest bite out of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge that mankind has taken in the last 2000 years. But most of such bites out of the apple have proved to be rather indigestible—usually for cybernetic reasons.’” Immediately after citing Brand citing Bateson’s bracing Biblical image for cybernetics from Steps to an Ecology of Mind, von Foerster singles out a passage from Brand’s chapter on Bateson that offers to explain to some extent why the fruit of cybernetics is so often hard to digest. So here is a nut for us to crack.

In this passage Bateson disparages the ingrained linear logic of the mainstream engineering mentality that loosely parrots cybernetic idioms while watering down their more profound revelations regarding autonomy, recursive processes, or self-referential operation—what Bateson may have in mind in this quote by “the philosophy of the feedback”: “The whole thinking that goes with the words ‘input’ and ‘output’ is monstrously bad,” he comments. “It draws a line across the systemic structure. . . . This actually throws away the whole cybernetic background for cybernetics, you know. . . . The input-output literature is very large, it’s highly skilled engineering and all the rest of it, but it ignores the philosophy of the feedback.”

Compare Francisco Varela in his 1976 CoEvolution Quarterly interview. Here Varela picks up Bateson’s critique of the input-output engineering mentality. He augments Bateson’s “philosophy of the feedback” through an explicit discourse of self-referential closure broadly applicable across a range of natural and artificial systems but fundamentally discerned in the organization and operation of biological systems:

As a matter of fact [Varela explains] a system is stable because of its closure of organization, that’s the source of its stability. Now this was already identified by Wiener, by his central concept of feedback. The notion of feedback is a self-referential one, but it was seized by the engineers who made it appear hierarchical. They apply a reference signal, identify input and output, and the output affects the input with a little delay. So the self-reference becomes hidden underneath, because of the trick of dealing with it in time. . . .

Following Bateson, Maturana, and von Foerster, Varela completes a major arc in the countercultural development of systems theory, as the most far-reaching discourses of cybernetics take upon themselves the second-order observation of recursive form and operational closure, the paradoxically synchronic circularity that undermines the diachronic linear ideology of mainstream control theory. One gets there, as Bateson himself suggests, self-referentially, by considering “the whole cybernetic background for cybernetics.” This would be akin to von Foerster’s “cybernetics of cybernetics”—the recursive semantic formula for second-order cybernetics, by another route. In the Cybernetic Countercultures, factoring different points of observation into the total picture of possible descriptions is no facile metaphysical gesture. Rather, it calls out and insists on the embodiment of cognitive systems, their embeddedness in fundamentally local organic affordances. It is these renovations of biological systems thinking that have taken the biggest “bite out of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge” at the heart of the cybernetic revelation.